Hey everyone! Welcome back to the Gubba podcast, I’m Gubba, a first time homesteader following in the footsteps of my homesteading forebears. In this podcast, I talk about homesteading, prepping, and everything in between.

Today, I want to talk to you about one of my favorite conspiracies—the world fairs. On the surface, these were massive international exhibitions meant to celebrate human progress, but when you look closer, they don’t quite add up. The speed of construction, the grandeur of the architecture, the technologies on display, and the way these entire “cities” vanished almost overnight—it all raises questions.

And when you tie in theories about a lost civilization known as Tartaria, the mud flood hypothesis, the idea of a Great Reset, and even the concept of aether energy, you start to see why the World Fairs have become a focal point for alternative historians and conspiracy researchers. By the end of this episode, you’ll see why so many people, myself included, are convinced that the official story of these fairs is hiding something much stranger.

The World Fairs: Cities That Appeared Overnight

Let’s begin with the basics. World Fairs, also known as expositions, took place across the world between the mid-1800s and early 1900s. These weren’t small events. They were massive undertakings that drew millions of visitors from across the world. Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exposition alone hosted over 27 million visitors in just six months—this at a time when the U.S. population was only about 63 million. Think about that: nearly half the country visited a single event.

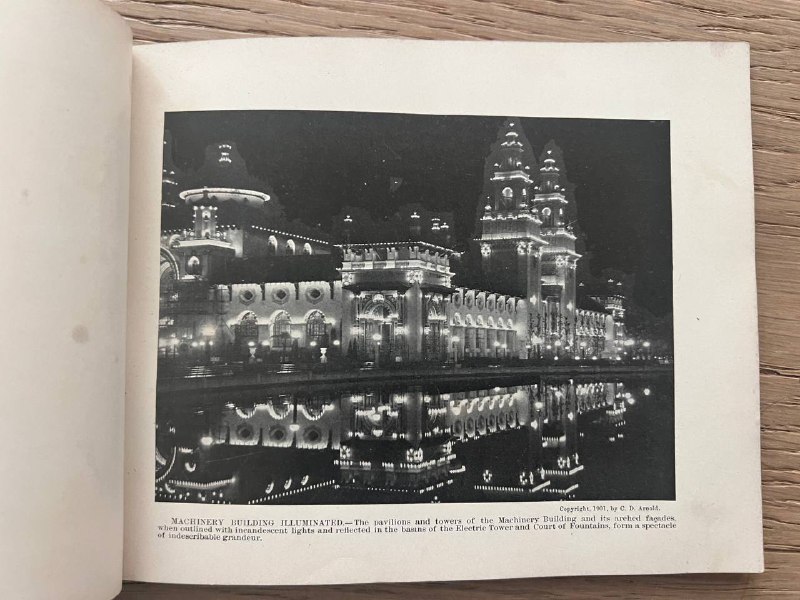

What made these fairs so remarkable were the buildings. Chicago’s fair was nicknamed the “White City” because its 200 new buildings were covered in a plaster-like material called “staff,” painted a uniform white. The result was dazzling: a city of domes, colonnades, and palaces that looked like it had been plucked straight out of ancient Rome or Athens. Visitors described walking into another world, one so beautiful and advanced it seemed to exist outside of time. At night, the entire city was illuminated with electric lights—something so new and overwhelming that many visitors wept at the sight.

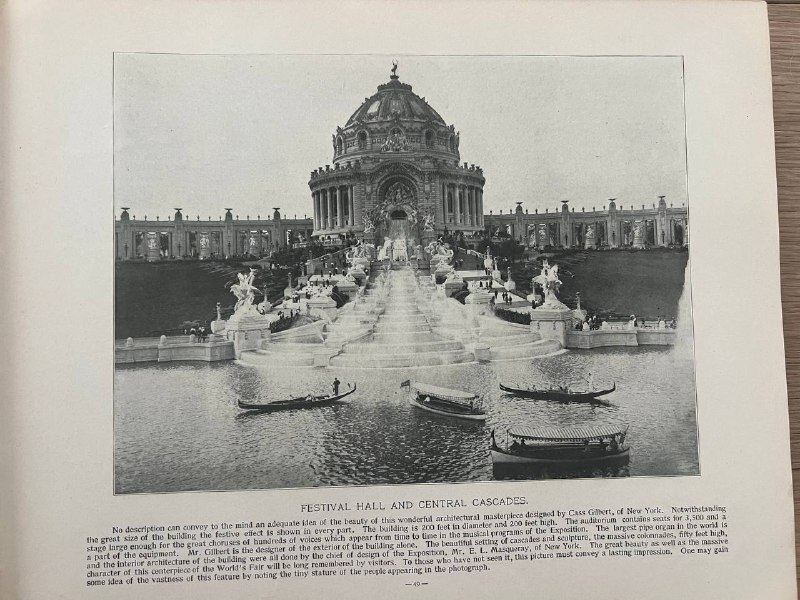

Here is just a snippet of one of the amazing canals at one of the world fairs.

Here’s the catch: we’re told these buildings were temporary, built cheaply, and torn down after the fair ended. And yet, when you look at photographs, the level of detail is stunning. These were not slapped-together sheds; they were fully formed works of architecture with intricate carvings, statues, and massive domes. And they were supposedly constructed in record time. Chicago’s fairgrounds were built in just two years, on swampy land that had to be drained and leveled first. Even with today’s technology, this would be a logistical nightmare. So how did they do it with horse-drawn carts and steam engines? This is the first oddity that makes people pause.

The Peculiar Pattern: Build, Bedazzle, Burn, and Erase

Now let’s talk about the pattern that shows up again and again. A city is built for a fair. It dazzles millions of visitors. It hosts new inventions, cultural exhibitions, and breathtaking architecture. And then, just as quickly as it appeared, it vanishes.

Take San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915. It featured grand palaces, colonnades, and the famous Tower of Jewels, decorated with over 100,000 colored glass “gems” that sparkled in the sunlight. The Palace of Fine Arts looked so permanent and majestic that visitors assumed it would become a fixture of the city. But within a year, almost everything was demolished or dismantled. Only the Palace of Fine Arts survived, and even it decayed until it had to be completely rebuilt in the 1960s.

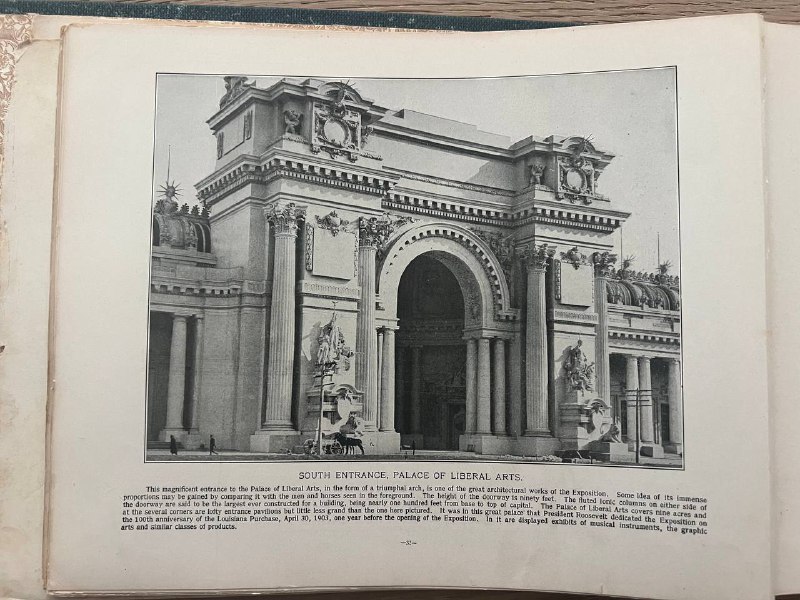

Look how ginormous this building is to the people and horses on the ground.

Or consider St. Louis in 1904. The Louisiana Purchase Exposition covered 1,200 acres and had nearly 1,500 buildings. It introduced the public to things like the ice cream cone, wireless telegraphs, and early x-ray machines. Yet within a few years, almost all of it was gone.

The pattern repeats in Buffalo, Paris, London, and dozens of other cities. Build a city. Bedazzle the world. Burn or bulldoze it. Erase it from the map, leaving behind only photographs and a handful of survivoring buildings. Why? The official answer is that these were temporary structures built for short-term use. But the conspiracy interpretation sees something else: an intentional erasure.

The Great Reset Hypothesis

This brings us to the Great Reset theory. According to this view, the World Fairs weren’t just celebrations of progress—they were tools to rewrite history. Imagine that there was once a global civilization with advanced knowledge of architecture, energy, and technology. Something happened—a disaster, a war, a deliberate takeover—that destroyed much of it. The survivors needed a new narrative, one that put them in control and explained away the remnants of the old world.

Enter the World Fairs. These events were, in this theory, carefully staged productions. Older buildings that had survived were covered in plaster facades to make them appear “new.” The fairs acted as introductions: here’s modern technology, here’s modern architecture, here’s the story of progress we want you to believe. Once the curtain fell, the “temporary” buildings were demolished, taking with them the physical evidence that these might not have been new at all.

The fairs served as a reset button. They told the public: this is the beginning of modern civilization. Forget what came before.

Mud Flood: The Buried Evidence

The mud flood hypothesis ties neatly into this idea. Have you ever walked past an old building and noticed that what looks like a full set of windows is buried below the ground level? Or that a grand doorway seems to lead straight into dirt? Mud flood theorists argue that these aren’t design quirks. Instead, they’re evidence that at some point, a massive event blanketed parts of cities in mud and sediment, burying entire floors of buildings.

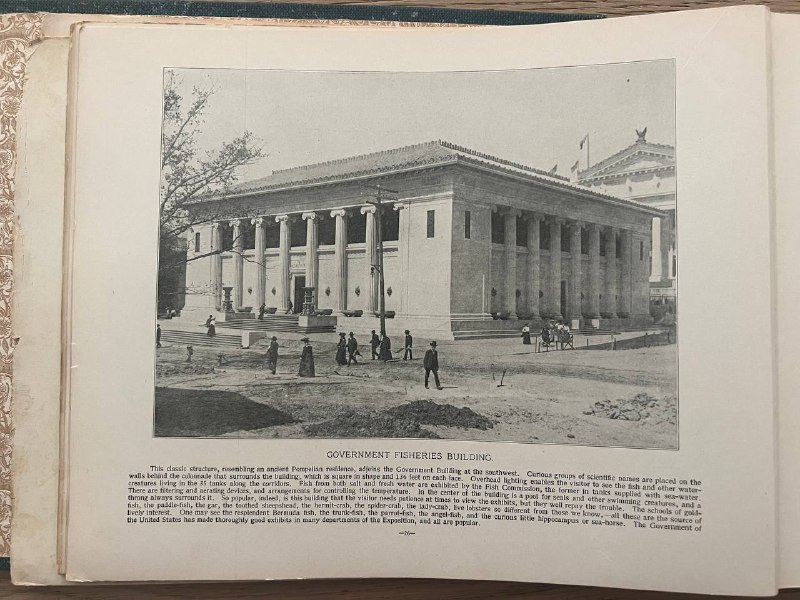

A common theme is the dirt roads surrounding these buildings. We are supposed to believe they pulled in the supplies across dirt and fields?

In this view, many of the buildings used for the World Fairs weren’t newly constructed at all. They were older Tartarian structures that had survived the mud flood. The “construction” for the fairs may have simply been digging them out, adding staircases to reach the new ground level, and putting fresh plaster facades on to make them appear as temporary fair buildings. Once the fairs ended, the structures could be demolished or reburied, hiding the evidence again.

This theory explains the speed of construction, too. If you’re not really building from scratch—if you’re just refurbishing existing buildings—it’s a lot easier to create a “new city” in a short time.

Tartaria: The Lost Civilization

Now let’s bring Tartaria into the picture. On old European maps, you’ll see vast areas of Asia labeled “Tartary.” Historians dismiss this as a vague term used for little-known lands. But in the conspiracy world, Tartaria is said to have been a vast, advanced civilization that spanned much of the earth.

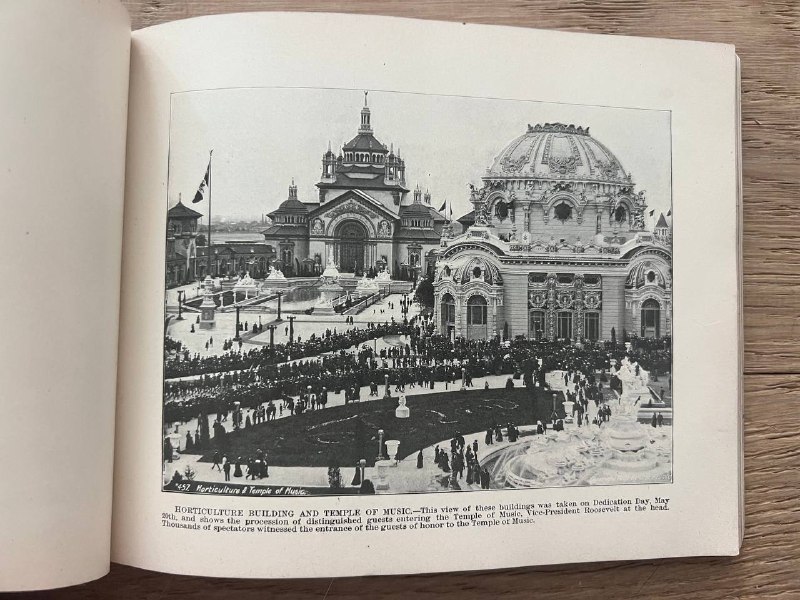

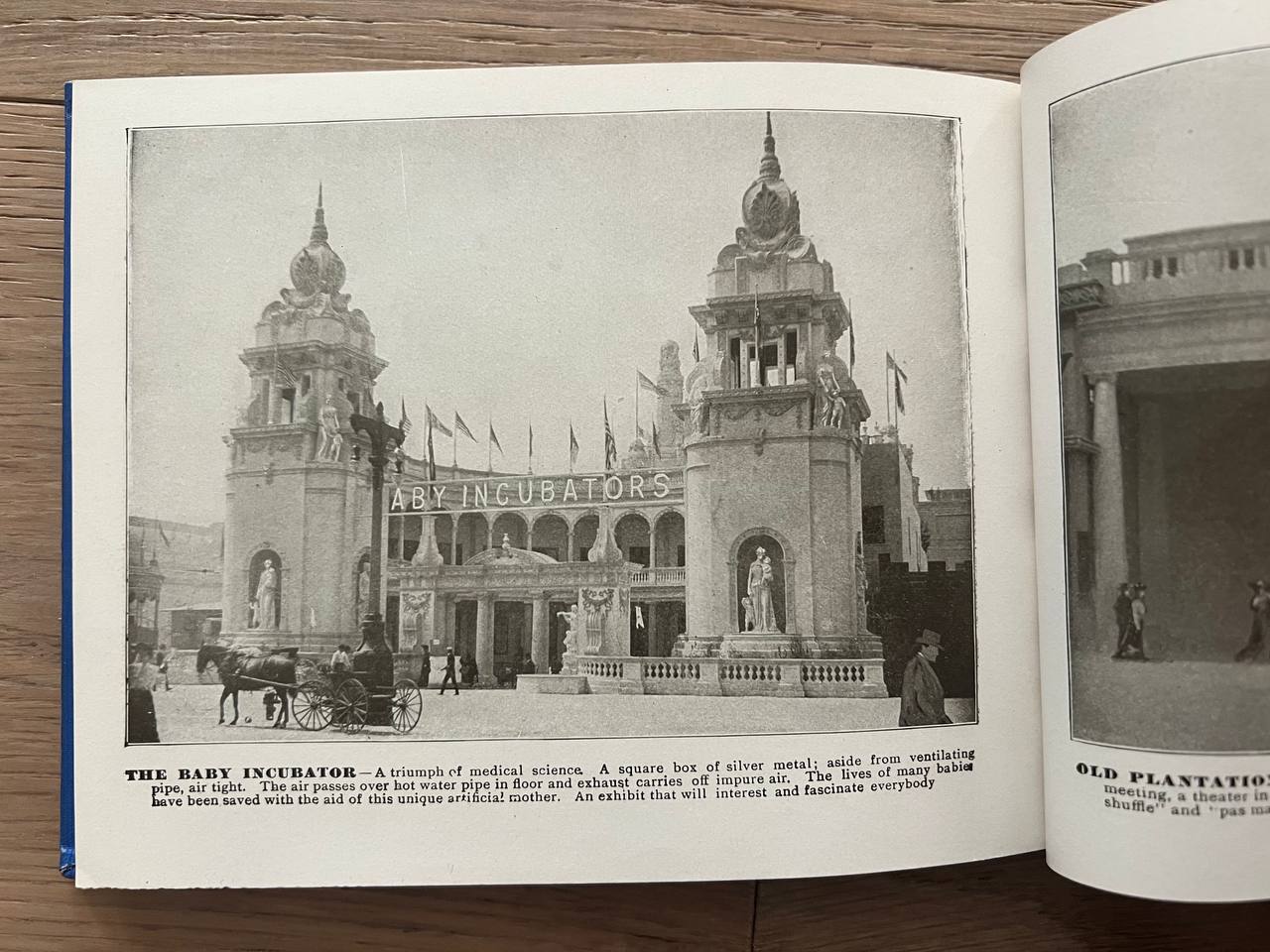

This photo is from the Buffalo, NY world fair. Look how massive the buildings are compared to the people.

Tartaria is credited with building the grand architecture we see all over the world—cathedrals, star forts, domes, and palaces that seem far beyond the capabilities of the societies we’re told built them. The idea is that Tartaria had a deep knowledge of energy systems, architecture, and possibly even free energy. When Tartaria fell, its history was erased, its buildings were repurposed, and its technologies were hidden. The World Fairs, in this story, were a way to reintroduce some of this architecture and technology under new labels, while quietly demolishing or hiding the rest.

This would explain why so many different cultures and countries suddenly started building in similar architectural styles in the 1800s—styles that appear global, not local. It would also explain why these fairs look less like “temporary exhibitions” and more like the staged rebranding of a civilization’s leftovers.

Aether: The Forgotten Energy

Now let’s talk about aether. In mainstream science, aether was a discarded theory, the invisible medium that light was once believed to travel through. After experiments failed to detect it, the idea was dropped. But in conspiracy circles, aether remains central.

The theory says that aether is real, and that older civilizations—including Tartaria—knew how to harness it as a form of free energy. Buildings with domes, spires, and intricate metal ornamentation weren’t just pretty—they were functional. They were energy collectors and transmitters, pulling power from the aether to light buildings, run machines, and maybe even heal the body.

This photo caught my eye in the book. Could this possibly be showing the aether? Other videos and photos with similar construction in modern day also capture this phenomenon.

At the Chicago World’s Fair, visitors were stunned by the glowing lights that covered the grounds. The official explanation is that it was powered by Westinghouse’s alternating current system, designed by Nikola Tesla. But some believe the architecture itself played a role—that the White City was wired into an older, hidden energy system. The fairs, in this sense, weren’t just showing off electricity—they were showing the public a piece of a lost technology, only to take it away again when the fair closed.

The Odd Inventions on Display

The architecture and lighting aren’t the only oddities. The fairs were also known for their unusual exhibits, many of which seem almost too advanced for their time. One of the most famous was the baby incubator exhibit. At multiple fairs, including Chicago and later at Coney Island, premature babies were displayed in glass incubators for the public to see. The incubators were presented as cutting-edge medical technology, but the fact that they were already functioning at public exhibitions suggests the technology may have been more established than we’re told.

Here is the Baby Incubator building from the Louisiana Purchase Exposition.

Other inventions introduced at fairs include x-ray machines, motion pictures, moving sidewalks, and wireless telegraphs. In many cases, these inventions appeared suddenly, as if pulled from nowhere, and were showcased to massive audiences as brand-new marvels. The conspiracy angle argues that these were not inventions being unveiled for the first time—they were older technologies being reintroduced at a controlled pace, framed as modern progress when in fact they may have been inherited knowledge.

Fires and Demolitions: Erasing the Evidence

Another recurring theme with the fairs is fire. Fires destroyed portions of the Chicago fairgrounds, including the Cold Storage Building, in spectacular fashion. Other fairs saw their grounds demolished or dismantled almost immediately after closing. Entire temporary cities were erased in months.

It’s easy to say this was just practicality—these were never meant to last. But in the conspiracy reading, fire and demolition serve a different role: erasure. If the fairgrounds contained evidence of older civilizations, or technologies that didn’t fit the official timeline, the easiest way to remove them was to burn or tear them down. Once gone, only photographs and written accounts remained, and those could be framed however the authorities wanted.

Why the World Fairs Matter in Conspiracy Thinking

So why do the World Fairs matter so much to conspiracy researchers? Because they sit at the intersection of several big ideas. They highlight anomalies in architecture, technology, and history. They tie into the theory of a Great Reset—the idea that history has been rewritten to erase evidence of older civilizations. They connect with the mud flood hypothesis, which explains the buried buildings we still see today. They link to Tartaria, the alleged lost empire.

And they fit with the theory of aether, a suppressed free energy source.

The fairs also matter because they were witnessed by millions of ordinary people. These weren’t secret experiments in hidden labs—they were massive public spectacles. If you wanted to reset public memory and roll out a new narrative of progress, there would be no better way than to dazzle the masses with breathtaking architecture, futuristic technologies, and glowing cities, then erase it all and tell them it was only temporary.

Closing Thoughts

When you put it all together, the World Fairs look less like temporary carnivals and more like staged productions. They were too big, too grand, too fast, and too thoroughly erased to fit comfortably into the official story. Maybe they were exactly what history says: massive exhibitions built quickly with plaster and wood, demolished because they weren’t meant to last. Or maybe they were something else entirely—a controlled reveal of older technologies and architectures, part of a broader plan to reset civilization’s memory and write a new version of history.

At the end of the day, what makes this theory so powerful isn’t that we have definitive proof—it’s that the photographs, the timelines, and the strangeness refuse to sit quietly. The glowing White Cities, the buried windows, the fires, the incubators, the domes and spires—they all whisper that history might not be what we’ve been told.

So next time you pass by an old building with windows sunk below ground, or see an ornate dome topped with a spire, or stumble across a photograph of the vanished White City, take a moment to ask yourself: was this just progress? Or was it part of a story we’ve only begun to rediscover?