Welcome back to the Gubba Podcast. I'm Gubba, a first time homesteader following in the footsteps of my homesteading forebears. I discuss everything from homesteading to prepping and everything in between. Today, we are going to be discussing a hot topic, the dragons vs. dinosaurs. Yes, believe it or not, this is a hot topic. When I question dinosaurs online, I get a lot of pushback. So let's dive in.

I want to start this episode by saying this clearly: the conversation about dragons versus dinosaurs isn’t silly, and it isn’t fringe. It’s uncomfortable. And that’s exactly why it’s mocked instead of debated. When a topic is dismissed rather than examined, it’s usually because it threatens a framework people rely on to make sense of the world.

What I want to do today is walk slowly through why many people believe dragons existed, why dinosaurs may be a modern reclassification rather than an ancient reality, and why this distinction matters far more than we’re told. Because this isn’t just about bones. It’s about history, memory, authority, and our relationship to creation itself.

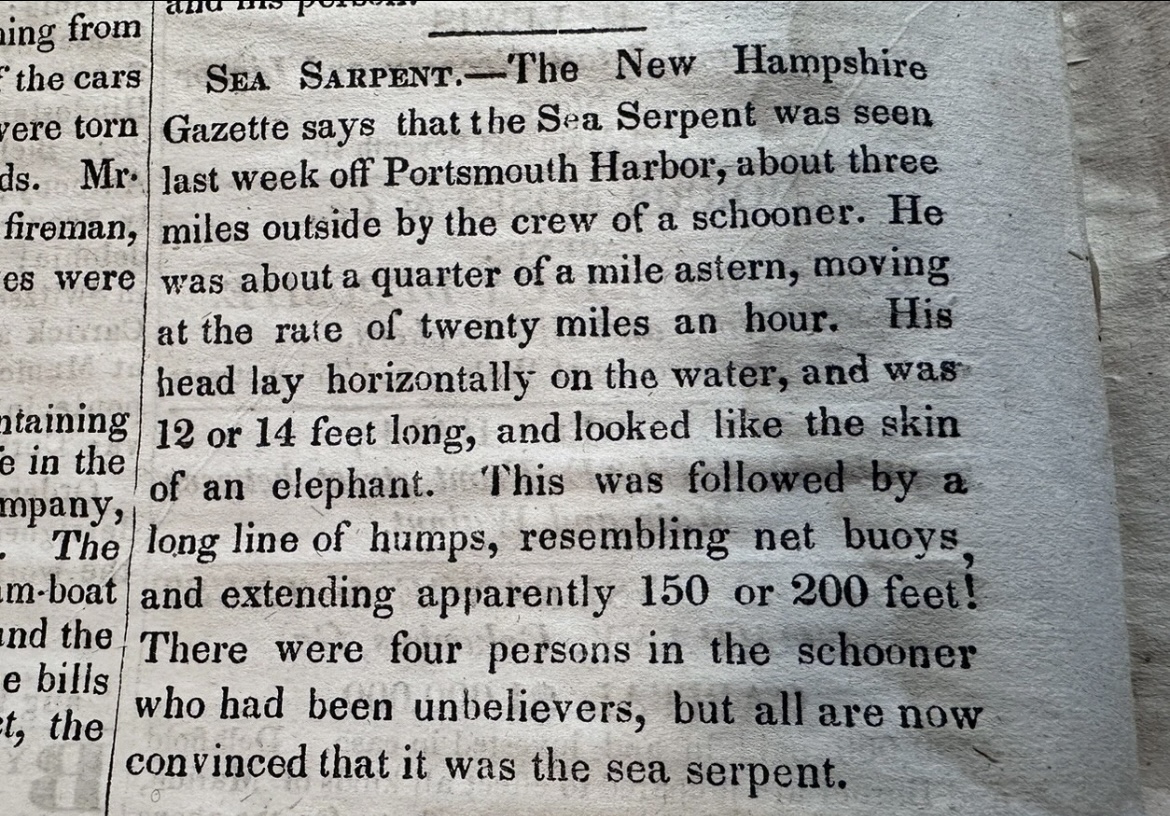

One of the strongest starting points is something incredibly simple: human testimony. Humans have been recording animals for as long as we’ve been writing. We documented predators and prey, dangers and migrations, extinctions and survival. And when you examine those records across civilizations, one thing becomes very clear. Humans remembered dragons. They did not remember dinosaurs. No ancient culture describes a Tyrannosaurus rex. No tablets, carvings, cave paintings, or written accounts warn about Triceratops or Stegosaurus. There are no instructions for avoiding them, hunting them, or protecting livestock from them. Yet dragons appear everywhere, across continents that had no contact with one another.

And it’s not just that dragons appear. It’s how they appear. China, Europe, Mesopotamia, Africa, the Americas, Australia—each describes large reptilian creatures with scales, long tails, wings or wing-like appendages, territorial behavior, and immense danger. The cultural framing varies, but the biological outline stays surprisingly stable. That kind of consistency is not how fictional mythology behaves. It is how eyewitness memory behaves—different voices describing the same kind of thing, from different angles, in different languages, with different theology around it.

Now let’s make this more grounded than just “everybody says it.” Because the strongest dragon-centric case isn’t built on vibes. It’s built on documented patterns where dragons are treated like part of the natural world. In medieval Europe, dragons show up in bestiaries—early natural-history style texts—alongside animals we all recognize. The category is telling: dragons weren’t filed under “imagination,” they were filed under “dangerous creatures.” That doesn’t prove every detail people believed about them, but it does show how seriously they were treated at the time.

China is even harder to brush off, because it’s not just stories— it’s material culture. “Dragon bones,” known as longgu, were collected, sold, and used in traditional medicine for centuries. This is documented historically and still discussed today as fossils and ancient bones that were traditionally considered dragon remains.

And what’s fascinating here is that the interpretation changed over time. The substance didn’t change. People were literally pulling “dragon bones” from the earth; later frameworks reclassified what those were. Even academic writing on “Dragon Bone Hill” discusses the long-standing belief that fossilized bones were dragon remains within Chinese tradition.

Then you have the Chinese zodiac, which is one of those quiet details that refuses to go away. Eleven animals are plainly real. The twelfth is the dragon. Dragon believers argue you don’t place a purely imaginary creature into a practical cultural system—used for timekeeping and identity—unless that creature is understood as real, or at least rooted in something real. You can call that symbolic, sure, but you still have to answer why that symbol and not a dozen other mythical animals. Why the dragon, specifically?

Now let’s flip to the other side of the debate—the dinosaur story—and talk about what is taught there. Dinosaurs are built around fossils. Fossils are real. The question is what story we’re attaching to them. And here’s one of the most important documented facts: the word Dinosaur was coined by Richard Owen in 1842.

The UC Museum of Paleontology also states the term was invented by Owen in 1842 to describe those “fearfully great reptiles.”

Dragon-centric thinkers lean on this point, not because they think bones appeared out of thin air in the 1800s, but because they argue the framework was standardized then. Before a framework is standardized, people interpret strange remains through the worldview they already have. For centuries, massive bones were interpreted as dragons, giants, and beasts. In the 1800s, those bones begin to be interpreted through deep time, extinction-before-man, and evolutionary progression. In other words, the bones didn’t change—the lens did.

And here is where museums become one of the most powerful “accidental witnesses” to the interpretive nature of the dinosaur narrative. Many people don’t realize how much of what they see in museums is cast, replica, or sculpted reconstruction. Museums aren’t hiding this—if you read the signage, it’s often right there—but the public experience still produces the impression of absolute certainty. The Field Museum has explained how casts are made from precise molds of fossils, and how missing bones can be sculpted when a fossil doesn’t exist for that part.

That means what you’re looking at is often a combination of “this is directly from a fossil mold” and “this section is an informed reconstruction.”

Dragon believers don’t have to claim museums are evil to make a strong point here. The point is simpler: the dinosaur narrative requires interpretation stacked on interpretation. A single bone fragment becomes a species. That species becomes a posture. That posture becomes behavior. That behavior becomes a timeline. That timeline becomes an entire worldview for children. And once it’s embedded culturally—movies, toys, classroom murals—it stops feeling like a model and starts feeling like memory. Dragons, by contrast, are memory first and model second.

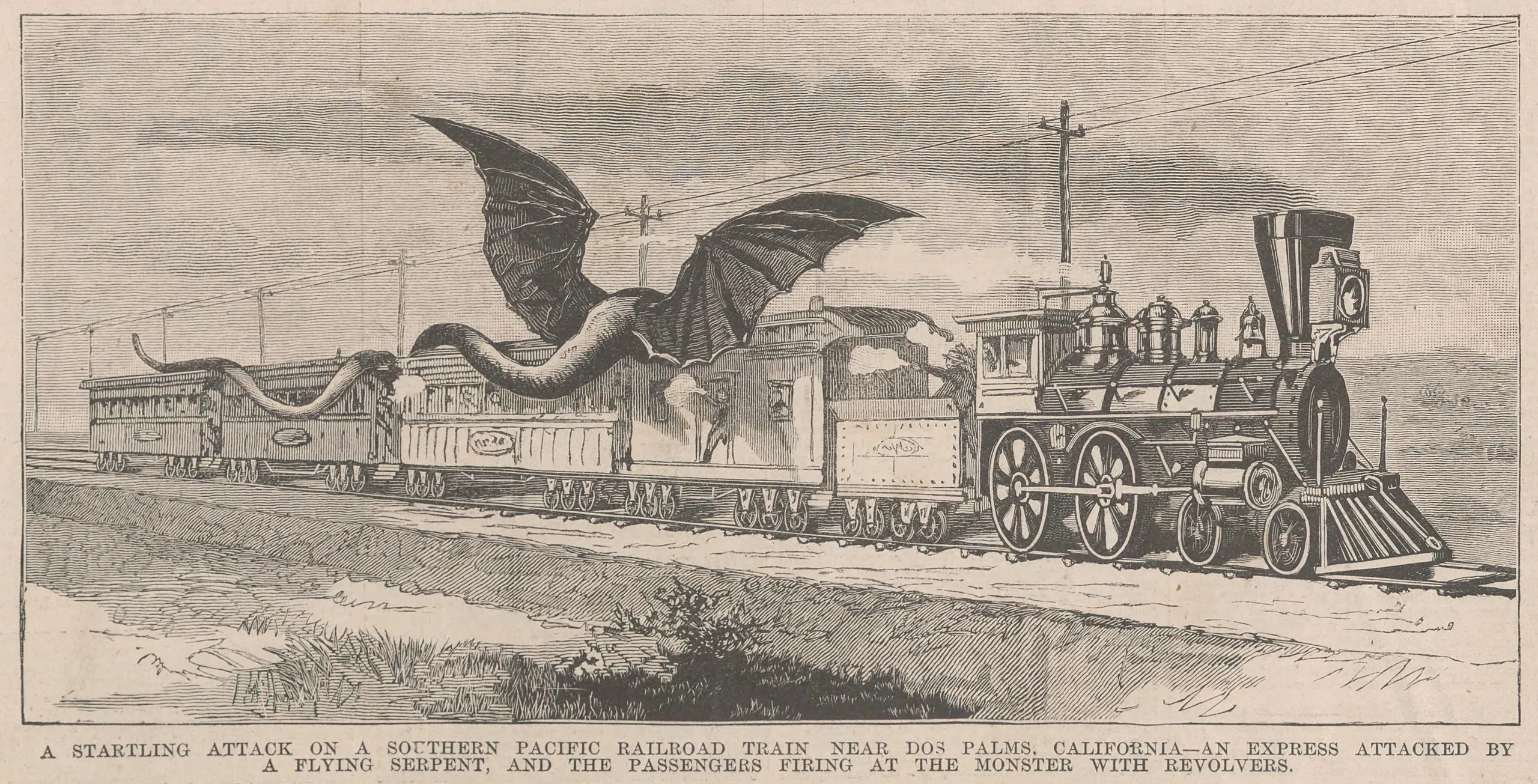

Now, let’s talk about the “modern-ish” accounts people cite—because the dragon argument gets strongest when it insists on continuity. Not “dragons only existed in mythic time,” but “dragons persisted into recorded history and were witnessed.” The most famous American example in this lane is the reported incident near Dos Palmos, California, in the early 1880s, often summarized as a winged serpent colliding with a train. Modern retellings trace it back to an 1882 Los Angeles Times report and describe railroad crew and passengers reporting a violent impact and describing a large airborne “flying snake.”

Nineteenth century newspapers sometimes printed sensational stories, exaggerations, and local tall tales. That is true. But here is the counterpoint dragon researchers make. You do not dismiss an entire category of reports just because some papers sensationalized. You evaluate patterns, consistency, and context.

In an era where journalists wrote down unusual events as matters of public curiosity, we are given a window into what people claimed to witness before modern institutions trained everyone to immediately self censor anything that contradicts the official natural history framework.

So the train story is not proof all by itself. What it is, is a cultural fracture line. It sits right where old world categories and modern categories collide. Witnesses describe something that fits ancient dragon outlines. Winged, serpent like, powerful, airborne. Modern people cannot even hold the category long enough to evaluate it because the dinosaur framework has already declared ahead of time what is allowed to exist.

That is the deeper point. The narrative does not merely interpret bones. It also polices what we are allowed to imagine is possible in the present.

And that brings us to the spiritual spine of this conversation. This is the reason this topic triggers people. The dinosaur narrative, as it is popularly taught, places death, suffering, predation, and extinction as the baseline reality long before humans ever enter the scene. It normalizes a death soaked earth prior to any moral story, any fall, any judgment, or any purpose.

It subtly trains the mind to accept randomness as fundamental and design as optional. And that absolutely affects how people relate to a Creator, because it relocates meaning into time and chance rather than intention.

Dragons do the opposite.

Dragons do not sit safely in an unreachable pre human void. Dragons appear inside human history. Inside moral frameworks. Inside religious texts. Inside warnings. Inside the kind of storytelling people use when they are trying to keep their children alive.

Dragons are not cute. They are not just animals. They represent a world that is bigger than us, more dangerous than us, and not fully controllable by us. They fit perfectly within a worldview where creation is real, spiritual reality is real, rebellion is real, and judgment is real.

And when dragons are defeated, driven out, or vanish, it is not gradual. It is catastrophic. That pattern matches ancient memory far more closely than slow, tidy extinction stories.

So the strongest dragon centered case, built from documented material, looks like this.

Dragons are remembered with consistent biological outlines. Dragons are treated as real in early natural history style writing. Dragon bones are a historically documented category of physical material in Chinese tradition, longgu, later reinterpreted under Western paleontological frameworks. And the dinosaur category itself is modern, formalized in the eighteen hundreds, and reinforced culturally through reconstructions that necessarily involve interpretation, casts, and fill ins.

And if you are listening to this and you feel that small spark of wait, why is this not even allowed as a conversation, hold onto that.

That spark matters.

Because the real battleground here is not bones versus stories. It is memory versus model. It is whether institutional consensus is treated as the final authority, or whether we are willing to admit that human history might preserve truths that modern frameworks tried to relabel out of existence.

I am not telling you to throw out every fossil find. I am telling you to notice how quickly dragons are treated like childish fantasy, while dinosaurs are treated like unquestionable memory. Even though one is anchored in widespread human testimony and the other is anchored in reconstruction layered on assumptions.

If dragons were real, the implications are massive. And when implications are massive, people do not argue gently. They enforce narratives.

That is why this conversation is not fringe.

It is threatening. And once you see that, you cannot unsee it.